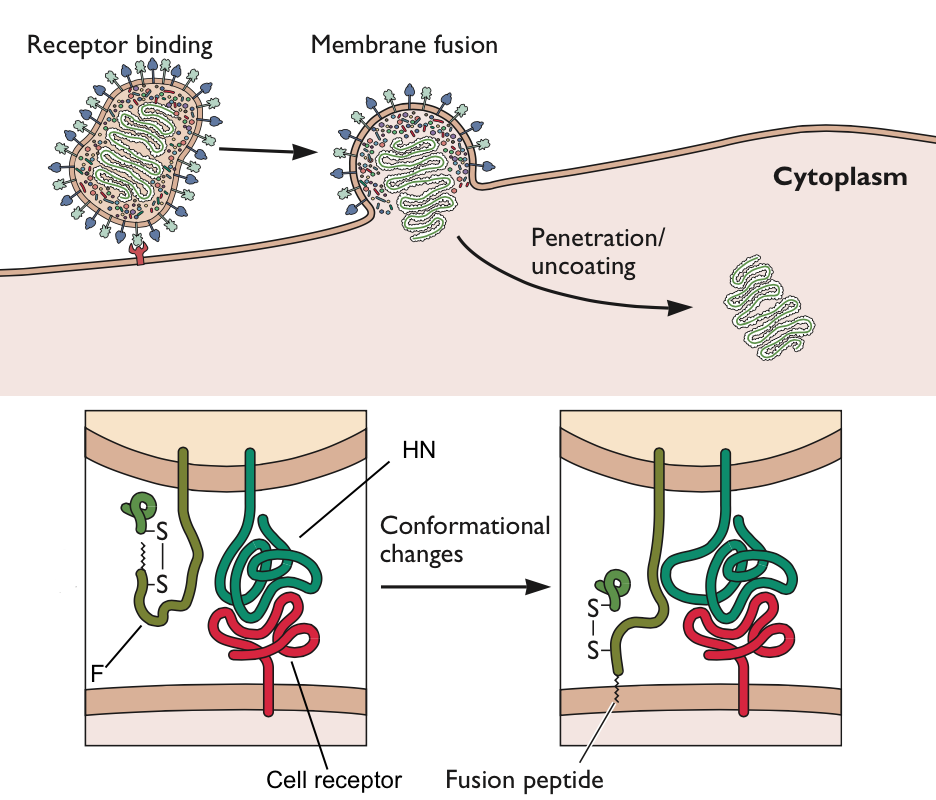

The entry of enveloped viruses into cells begins when the membrane that surrounds these virus particles fuse with a cell membrane. The process of virus-cell fusion must be tightly regulated, to make sure it happens in the right cells. The fusion activity of measles viruses isolated from the brains of AIDS patients is not properly regulated, which might explain why these viruses cause disease in the central nervous system.

Measles virus particles bind to cell surface receptors via the viral glycoprotein HN (illustrated). Once the viral and cell membranes have been brought together by this receptor-ligand interaction, fusion is induced by a second viral glycoprotein called F, and the viral RNA is released into the cell cytoplasm. The N-terminal 20 amino acids of F protein are highly hydrophobic and form a region called the fusion peptide that inserts into target membranes to initiate fusion. Because F-protein-mediated fusion can occur at neutral pH, it must be controlled, to ensure that virus particles fuse with only the appropriate cell, and to prevent aggregation of newly made virions. The fusion peptide of F is normally hidden, and conformational changes in the protein thrust the it toward the cell membrane (illustrated). These conformational changes in the F protein, which expose the fusion peptide, are thought to occur upon binding of HN protein to its cellular receptor.

During a recent outbreak of measles in South Africa, several AIDS patients died when measles virus entered and replicated in their central nervous systems. Measles virus normally enters via the respiratory route, establishes a viremia (and the characteristic rash) and is cleared within two weeks. The virus is known to enter the brain in up to half of infected patients, but without serious sequelae. The measles inclusion body encephalitis observed in these AIDS patients typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals several months after infection with measles virus.

Measles virus isolated postmortem from these two individuals had a single amino acid change in the F glycoprotein, from leucine to tryptophan at position 454. This single amino acid change allowed viruses to fuse with cell membranes without having to first bind a cellular receptor via the HN glycoprotein. In other words, the normal mechanism for regulating measles virus fusion – binding a cell receptor – was bypassed in these viruses. This unusual property might have allowed measles virus to spread throughout the central nervous system, causing lethal disease.

How did these mutant viruses arise in the AIDS patients? Because these individuals had impaired immunity as a result of HIV-1 infection, they were not able to clear the virus in the usual two weeks. As a consequence, the virus replicated for several months. During this time, the mutation might have arisen that allowed unregulated fusion of virus and cell, leading to unchecked replication in the brain. Alternatively, the mutation might have been present in virus that infected these individuals, and was selected in the central nervous system.

An interesting question is whether these neurotropic measles viruses can be transmitted by aerosol between hosts – a rather unsettling scenario. Fortunately, we do have a measles virus vaccine that effectively prevents infection, even with these mutant viruses.